Do I Have Anorexia? 10 Warning Signs to Recognize

Rena Shoshana Forester is a Yoga teacher, Health & Wellness Coach, and mentor with nearly 12 years of professional international experience. She founded Wellness Edge for Hi-Tech companies, Karuna Yoga for trauma-survivors (primarily children), and teaches Yoga certification courses. Rena Shoshana empowers individuals to navigate their healing journeys by cultivating self-awareness, fostering self-compassion, and implementing sustainable, practical tools - one step at a time. She is deeply grateful to contribute to Recovery.com, whose mission resonates closely with her own.

Rena Shoshana Forester is a Yoga teacher, Health & Wellness Coach, and mentor with nearly 12 years of professional international experience. She founded Wellness Edge for Hi-Tech companies, Karuna Yoga for trauma-survivors (primarily children), and teaches Yoga certification courses. Rena Shoshana empowers individuals to navigate their healing journeys by cultivating self-awareness, fostering self-compassion, and implementing sustainable, practical tools - one step at a time. She is deeply grateful to contribute to Recovery.com, whose mission resonates closely with her own.

Anorexia nervosa is a deeply paradoxical disorder. What begins as an attempt to control the body often results in the mind losing control.

Far more than simply refusing to eat, anorexia nervosa is characterized by an intense fear of gaining weight, extreme restriction of food intake, and a distorted body image, often leading to dangerous weight loss and physical and psychological consequences.

It fundamentally disrupts a person’s relationship with nourishment, transforming it into a source of anxiety, guilt, and self-punishment.

This illness carries one of the highest mortality rates among psychiatric disorders and often coexists with other mental health conditions such as anxiety, depression, or obsessive-compulsive disorder.

What Is Anorexia?

Clinically, anorexia nervosa1 is diagnosed using criteria outlined in the DSM-5-TR, which includes persistent restriction of caloric intake, significantly low body weight, intense fear of gaining weight,2 and a distorted perception of body image or failure to recognize the seriousness of low weight.

The disorder is further categorized by severity based on body mass index (BMI),3 though recent studies suggest that this numerical scale captures only part of the picture. Updates in diagnostic criteria have led to a 60% increase in lifetime prevalence estimates, underscoring how many people may have previously gone undiagnosed and untreated.

In anorexia nervosa, the pursuit of control becomes the ultimate loss of control, where the quest for perfection becomes a dance with self-destruction.

More than simply “not eating,” anorexia nervosa is a complex psychiatric illness associated with food restriction and high mortality that transforms the fundamental human relationship with nourishment into a battlefield of the mind.

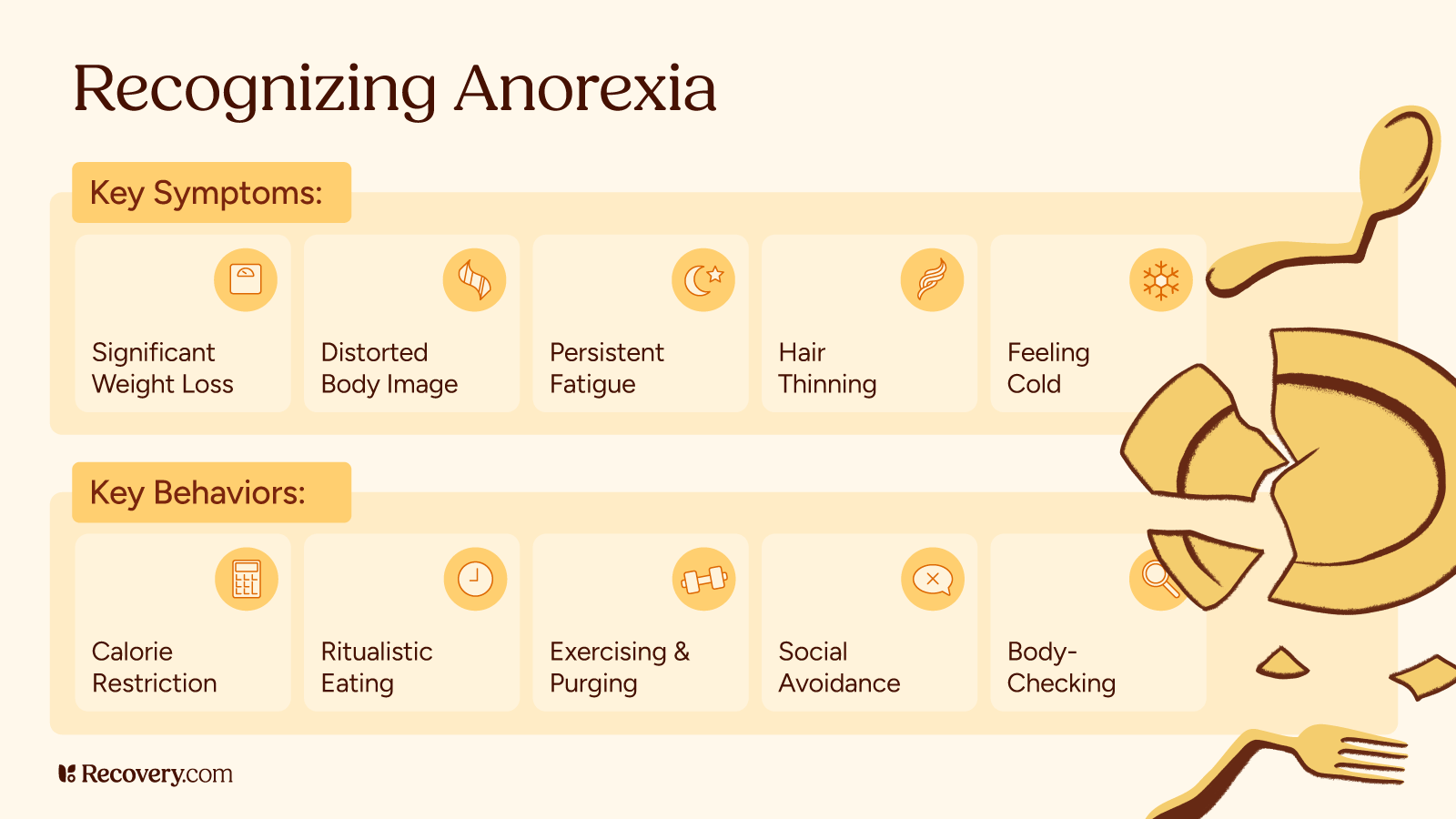

Clinical Symptoms

According to the DSM-5-TR,4 anorexia nervosa is clinically defined by three core criteria that paint only the surface of this enigmatic disorder. Healthcare providers diagnose anorexia nervosa based on the criteria listed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5-TR).

The three criteria include:

- Self-induced calorie restriction, leading to significant weight loss or a failure to gain weight in growing children, accompanied by typically, a low body weight based on age, sex, height and stage of growth,

- Abnormal obsession with body weight and intense fear of gaining weight or becoming “fat”

- Distorted self-image or an inability to acknowledge the seriousness of their condition.

The disorder’s severity is now classified using BMI thresholds:

Mild: BMI greater than or equal to 17 kg/m2

Moderate: BMI 16–16.99 kg/m2

Severe: BMI 15–15.99 kg/m2

Extreme: BMI less than 15 kg/m2

However, these numbers tell only part of the story—recent research reveals that the lifetime prevalence of anorexia nervosa increased by 60% using the new DSM-5-TR definition, highlighting how many individuals previously suffered in diagnostic shadows.

Anorexia is a mental illness typically rooted in deeply ingrained emotional patterns, where controlling food intake and body image can become almost addictive, often leaving you feeling depleted. Recovery takes dedication and patience; with steady effort, you can develop a healthier relationship with yourself and your body.

Here are 10 symptoms and signs of anorexia that you might notice in yourself or a loved one.

Explore Eating Disorders Treatment Centers

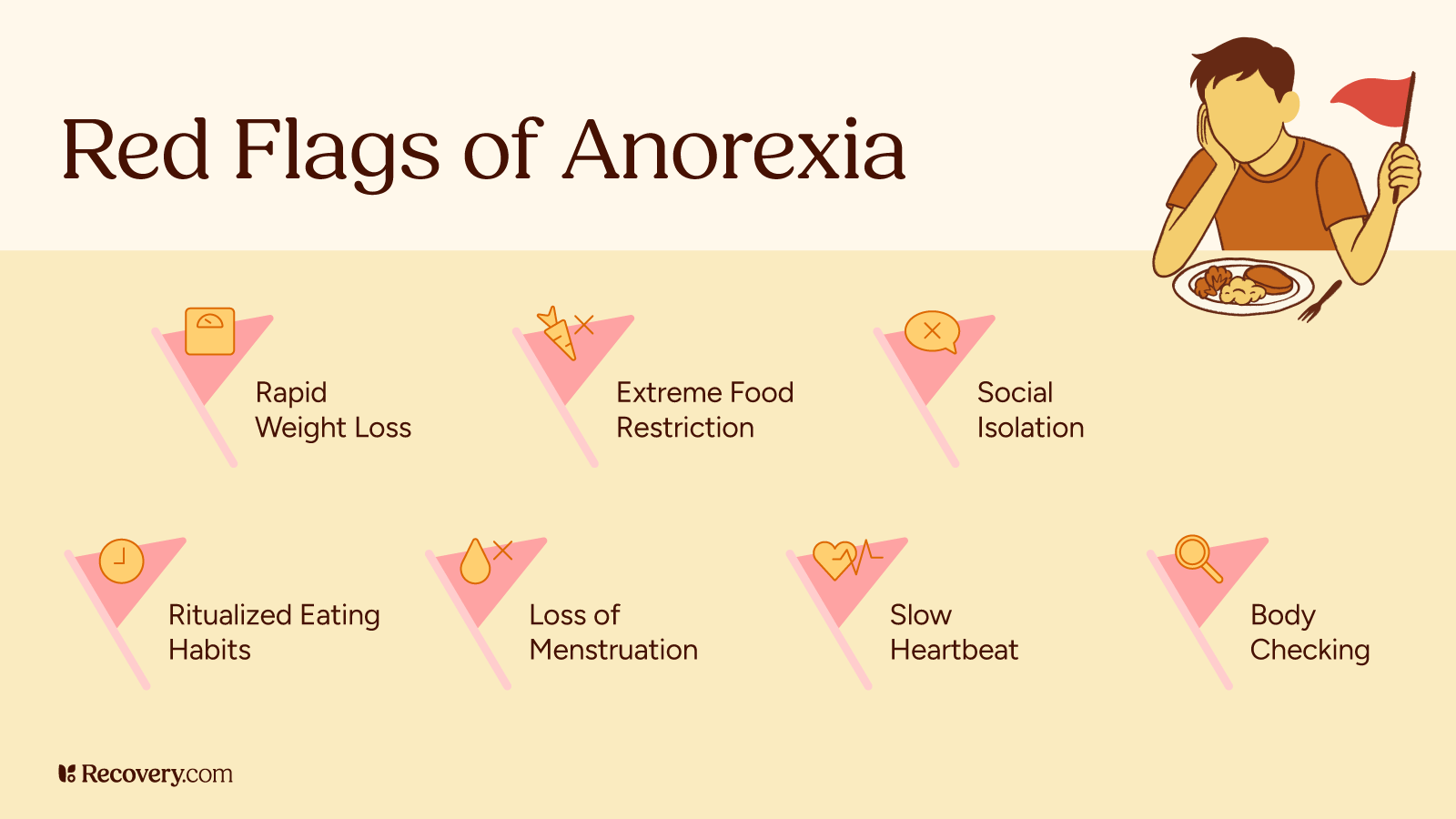

1. Fear of Weight Gain

An intense fear of gaining weight, despite being underweight, is a key symptom of anorexia. This fear often leads to extreme avoidance of certain foods, purging, or using laxatives.

A fear of gaining weight can look like avoiding foods you think are, “fattening,” taking laxatives as a way to temporarily reduce water-weight from the body, and/or purging. The fear of weight gain and desire to maintain a low body weight can become an obsession.

This fear of gaining weight stems from a distorted body image and an overwhelming preoccupation with weight and appearance.5 This fear is essentially an attempt to establish control over your life and appear perfect. Underlying psychological factors such as anxiety or low self-esteem also play a role.

Maintaining weight loss, though a form of malnutrition, can become a way to feel a distorted sense of achievement over your life.

The sense of control gained from restricting food can temporarily mask emotional pain or discomfort, requiring proper eating disorder treatment in order to break free from the cycle.

2. Extreme Weight Loss

Extreme and unexplained weight loss6 can be a warning sign of anorexia, leading to malnutrition and serious health risks. If your weight loss is unexplained, it could be a symptom of anorexia, bulimia nervosa, atypical anorexia, binge eating disorder, or other health problems.

Medical professionals generally agree that losing more than 5% of your body weight within a 6-12 month period is considered extreme. This means that a person with a healthy weight of 160 lbs would lose 8 lbs (dropping to 152 lbs), or someone with a healthy weight of 200 lbs would lose 10 lbs (dropping to 190 lbs) in 6-12 months.

Such drastic weight changes, especially when not intentional or accompanied by a clear medical reason, can indicate an underlying health issue, including eating disorders.

If you or someone you know is experiencing significant weight loss without a clear cause, it’s crucial to seek medical advice as early intervention can be key to recovery.

3. Excessive Exercise

Too much of anything is rarely beneficial. Continuing to exercise despite physical exhaustion or injury can be a sign of anorexia nervosa.

Excessive exercise,7 even when tired or injured, is a common symptom of anorexia. It’s often driven by a need to control body image rather than improve physical fitness. Additionally, a high level of exercise may stem from a deep-seated fear of weight gain or it may be tied to underlying issues such as anxiety and low self-esteem.

In many cases, the drive to exercise excessively is not about improving physical fitness, but rather about maintaining a sense of control over one’s body.

Over time, this can lead to physical harm (like stress fractures or cardiovascular strain) and extreme exhaustion. Exercising may even take priority over social functioning, work, and/or school commitments.

Recognizing the psychological motivations behind excessive exercise is important for determining an appropriate treatment plan.

4. Distorted Body Image

If you look in the mirror and perceive yourself as overweight, despite being dangerously underweight, you may have anorexia nervosa.

This distorted body image or body dysmorphia is central to anorexia and can drive you to continue restricting food intake, even when faced with obvious health consequences.

Body dysmorphia8 is or body dysmorphic disorder (BDD), is a mental health condition in which individuals become preoccupied with perceived flaws or perceived defects in their appearance. This preoccupation can cause significant emotional distress and interfere with daily functioning.9

BDD is classified under obsessive-compulsive and related disorders in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5). It affects both men and women and often begins in adolescence, a period when appearance-related concerns tend to intensify.

Your distorted body image may be influenced by cultural or familial beliefs about what the “ideal” body looks like. Social media10 is also impacting body image and playing a contributing role in the development of eating disorders, specifically for adolescents. While you may believe you’re simply trying to maintain an “ideal” appearance, this behavior can lead to dangerous malnutrition.

The disconnect between how you see yourself and reality can make it difficult to seek help, as you might not recognize the seriousness of your condition. A trusted healthcare provider can help you recognize the signs and find a healthier path.

5. Restriction of Food Intake

Severe limitation of food intake, such as skipping meals, eating very small amounts, or using supplements as meal replacements, can lead to malnutrition and even life-threatening health conditions. This restriction is often driven by a fear of gaining weight and a need for control.

If your food restriction stems from an attempt to exert control or define your self-worth through food, you may have anorexia nervosa. In such cases, mental health professionals are essential to support your healing and recovery.

However, if you avoid certain foods due to sensory characteristics like taste, texture, or smell, or because of a negative past experience (such as choking), it is more likely that you have Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder (ARFID).11

Unlike anorexia, individuals with ARFID do not have a distorted body image or a fear of gaining weight. While ARFID can still lead to nutritional deficiencies, it is not driven by a desire to lose weight.

The Neurobiology of Restriction

Anorexia nervosa is fundamentally a complex neuropsychological disorder12 where the brain itself becomes rewired.

Research reveals that among individuals with AN, dorsal front striatal circuits play a greater role in guiding decisions regarding what to eat than among healthy individuals. This means that food choices become driven more by rigid, habit-based neural pathways than by the flexible reward systems that typically govern eating.

The disorder involves gray and white matter reduction13 correlating with the extent of malnourishment and is mostly reversible with recovery. At the same time, functional brain imaging shows increased amygdala activation and altered cingulate cortex activation when patients encounter food-related stimuli. The altered dopamine status of patients with anorexia may result from a brain abnormality that underlies the disorder, suggesting that neurobiological differences may precede rather than result from the starvation process.

6. Preoccupation With Food

Even if you refuse to eat, you may still have obsessive thoughts about food, dieting, and body weight. These thoughts can be all-consuming and constantly present. You might also engage in activities such as counting calories or categorizing foods as “safe,” “dangerous,” “good,” or “bad.”

This preoccupation with food is often linked to the obsessive-compulsive tendencies that frequently accompany anorexia. It may lead you to fixate on eating behaviors, avoid certain food groups, or excessively research food-related topics. These behaviors can reinforce your disordered relationship with food and make it more difficult to focus on other aspects of life.

This obsessive thinking about food, dieting, and body image can become all-consuming. Seeking professional help is essential to break the cycle of obsession and establish a healthier relationship with food.

7. Physical Symptoms

Anorexia nervosa causes devastating physical effects14 throughout the body as malnutrition and starvation take their toll on every organ system. Starvation induces protein and fat catabolism that leads to loss of cellular volume and function, resulting in adverse effects on, and atrophy of, the heart, brain, liver, intestines, kidneys, and muscles.

Additional physical symptoms may help indicate anorexia: fatigue, dizziness, bloating, constipation, hair thinning, brittle nails, osteoporosis, anemia, and the loss of menstrual periods (amenorrhea) in women.

These symptoms are direct consequences of malnutrition15 and extreme food restriction. When the body does not receive adequate nutrition, it slows down many of its functions in an attempt to conserve energy, compromising overall physical health.

Specifically, fatigue and dizziness16 can be linked to low blood pressure, a direct result of malnutrition. Hair thinning and brittle nails are also signs that the body is not getting the necessary nutrients for healthy growth and repair, further affecting physical health.

Osteoporosis and anemia are also common results of long-term malnutrition, as the body prioritizes basic functions over bone and blood health. Hormonal imbalances, including the loss of menstrual periods (amenorrhea) in women, occur as the body prioritizes survival over reproductive function, reducing the production of key hormones like estrogen.

These physical changes are signals that the body is struggling to function properly due to extreme malnutrition, which makes early intervention crucial, highlighting the importance of early intervention to protect long-term physical health.

8. Feelings of Control

From the outside, anorexia nervosa may appear disorganized, with behaviors that don’t seem to make sense.

However, if you are struggling with anorexia and feeling overwhelmed in other areas of your life, you might believe that controlling your eating behaviors provides a sense of stability. When everything else feels chaotic, restricting food intake can seem like the only way to assert control.

This need for control may offer temporary relief but is often misguided. Over time, this obsession with control can deepen feelings of anxiety and isolation. Ultimately, this false sense of control perpetuates the cycle of anorexia, which is why proper intervention is crucial for recovery.

A trusted healthcare provider like a dietitian or psychotherapist can help you to break free from the cycle. If you feel fear creep in as you go to take the first step towards finding the appropriate eating disorder treatment for you, remember to take it one step at a time.

9. Social Withdrawal

Social withdrawal is a common symptom of anorexia nervosa. This can look like distancing yourself from your friends, family members, and/or social activities. Often feelings of shame, embarrassment, or a fear of being judged for eating habits and body image issues fuel isolating behaviors.

Social situations, especially those involving food, can trigger anxiety or discomfort, leading to a desire to avoid gatherings altogether.

This isolation can be both a result of the disorder and a contributing factor to its progression. As you withdraw, you may feel increasingly alone and disconnected, which can exacerbate feelings of depression or anxiety.

The lack of support from loved ones can make it harder to recognize the need for help or to seek medical care, ultimately perpetuating the cycle of anorexia.

10. Perfectionism

Many individuals with anorexia nervosa exhibit perfectionistic tendencies; perhaps you set extremely high and often unrealistic expectations for yourself.

While this drive for perfection may be particularly prominent in your eating habits, it likely extends into other areas of your life, too. Maybe you strive to achieve academic or professional achievements, constantly pushing yourself to meet unattainable expectations. When you inevitably fall short, you feel guilty, like a failure, and self-criticise.

With regard to body image, you may become obsessed with achieving a thin or lean body, believing that it is an “ideal” body shape. This desire to achieve a certain body shape leads to rigid and inflexible eating habits.

If you constantly strive for unrealistic standards of beauty or achievement, you might experience guilt or self-criticism when you don’t meet them. Psychotherapy and/or nutrition counseling can provide you with the space to work toward developing healthier, more flexible perspectives on eating habits, body image, and self-worth.

Ready to Take the First Step Toward Healing?

If you or a loved one may be struggling with anorexia nervosa, you are not alone. Help is available. Explore qualified eating disorder treatment programs near you that provide compassionate care, personalized support, and proven paths to recovery.

Find eating disorder treatment options near you today.

FAQs

Q: How do I know if I’m anorexic?

A: Anorexia is characterized by an extreme fear of gaining weight, severe food restriction, and a distorted body image. Key signs include drastic weight loss, excessive exercise, and obsession with food.

Q: What are 4 signs of anorexia?

A: Four common signs of anorexia include extreme weight loss, excessive exercise, distorted body image, and obsessive thoughts about food and dieting.

Q: What qualifies you as an anorexic?

A: To be diagnosed with anorexia, one typically restricts food intake, fears gaining weight, and has a distorted view of their body. These behaviors often lead to severe physical and emotional health consequences.

Q: What is anorexia nervosa?

A: Anorexia nervosa is an eating disorder characterized by an intense fear of gaining weight and a distorted body image, which leads individuals to restrict food intake severely. This can result in extreme weight loss, malnutrition, and severe physical and emotional health issues. Treatment from healthcare professionals is crucial for recovery.

Q: What are the signs and symptoms of anorexia?

A: Common signs of anorexia include extreme weight loss, excessive exercise, distorted body image, social withdrawal, obsession with food and dieting, and various physical symptoms like hair thinning, brittle nails, and hormonal imbalances. If you recognize these signs, seeking professional help is essential.

Q: Can I have anorexia if I’m not underweight?

A: Yes, anorexia can be present even in people who are not underweight. The key factor is the overwhelming fear of gaining weight and the extreme restrictions placed on food intake, which may still harm physical and mental health.

Q: Can I have anorexia if I still eat regularly?

A: Even if you eat regularly, you can still have anorexia if the food choices are extremely restrictive, and the primary goal is weight loss or maintaining an unnaturally low body weight. The key lies in the underlying fear of gaining weight and a distorted body image.

-

Smink, F. R. E., van Hoeken, D., & Hoek, H. W. (2012). Epidemiology of eating disorders: Incidence, prevalence and mortality rates. Current Psychiatry Reports, 14(4), 406–414. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-012-0282-y

-

Bozzola, E., Cirillo, F., Mascolo, C., Antilici, L., Raucci, U., Guarnieri, B., Ventricelli, A., De Santis, E., Spina, G., Raponi, M., Villani, A., & Marchili, M. R. (2024). Predisposing Potential Risk Factors for Severe Anorexia Nervosa in Adolescents. Nutrients, 17(1), 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17010021

-

Kazdin, A. E., Fitzsimmons-Craft, E. E., & Wilfley, D. E. (2017). Addressing critical gaps in the treatment of eating disorders. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 50(3), 170–189. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22670

-

National Eating Disorders Association. (n.d.). Anorexia nervosa. National Eating Disorders Association. https://www.nationaleatingdisorders.org/anorexia-nervosa

-

American Psychological Association. (n.d.). Eating disorders. In APA dictionary of psychology. https://www.apa.org/topics/eating-disorders

-

Charrat, J.-P., Massoubre, C., Germain, N., Gay, A., & Galusca, B. (2023). Systematic review of prospective studies assessing risk factors to predict anorexia nervosa onset. Journal of Eating Disorders, 11, 82. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-023-00882-0

-

Mond, J. M. (2021). “Excessive exercise” in eating disorders research: Problems of definition and perspective. Eating and Weight Disorders - Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity, 26(4), 1017–1020. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-020-01075-3

-

Singh, A. R., & Veale, D. (2019). Understanding and treating body dysmorphic disorder. Indian journal of psychiatry, 61(Suppl 1), S131–S135. https://doi.org/10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_528_18

-

Kuck, N., Cafitz, L., Bürkner, P.-C., Hoppen, L., Wilhelm, S., & Buhlmann, U. (2021). Body dysmorphic disorder and self-esteem: A meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry, 21, 310. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-021-03305-7

-

Suhag, K., & Rauniyar, S. (2024). Social Media Effects Regarding Eating Disorders and Body Image in Young Adolescents. Cureus, 16(4), e58674. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.58674

-

Moini, J., LoGalbo, A., & Ahangari, R. (2024). Eating disorders. In Foundations of the mind, brain, and behavioral relationships: Understanding physiological psychology (pp. 353–367). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-323-95975-9.00023-8

-

Steinglass, J. E., & Walsh, B. T. (2016). Neurobiological model of the persistence of anorexia nervosa. Journal of Eating Disorders, 4, 19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-016-0106-2

-

Grey Matters Journal. (n.d.). Anorexia. Grey Matters Journal. https://greymattersjournal.org/anorexia/

-

Cost, J., Krantz, M. J., & Mehler, P. S. (2020). Medical complications of anorexia nervosa. Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine, 87(6), 361–366. https://doi.org/10.3949/ccjm.87a.19084

-

Miskovic-Wheatley, J., Bryant, E., Ong, S. H., Vatter, S., Le, A., National Eating Disorder Research Consortium, Touyz, S., & Maguire, S. (2023). Eating disorder outcomes: findings from a rapid review of over a decade of research. Journal of eating disorders, 11(1), 85. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-023-00801-3

-

Yahalom, M., Spitz, M., Sandler, L., Heno, N., Roguin, N., & Turgeman, Y. (2013). The significance of bradycardia in anorexia nervosa. The International journal of angiology : official publication of the International College of Angiology, Inc, 22(2), 83–94. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0033-1334138

Our Promise

How Is Recovery.com Different?

We believe everyone deserves access to accurate, unbiased information about mental health and recovery. That’s why we have a comprehensive set of treatment providers and don't charge for inclusion. Any center that meets our criteria can list for free. We do not and have never accepted fees for referring someone to a particular center. Providers who advertise with us must be verified by our Research Team and we clearly mark their status as advertisers.

Our goal is to help you choose the best path for your recovery. That begins with information you can trust.