What Causes Depression? 8 Common Causes That Demystify Depression

Why is this happening to me?

Many people with depression ask themselves this question—repeatedly. So, is there a cause? And if you find it, can you pluck it like a weed and get better?

Though healing isn’t often that simple, depression does have a cause and it is treatable. And it’s okay if you can’t identify a cause for your depression, too. Treatment can be just as effective for people who know exactly why they’re depressed and the ones who have no idea.

The causes of depression will vary widely from person to person. But for each cause–whether it’s genetics, environment, situations, or anything else–you have resources to heal.

What Is Depression?

Depression is a mental health condition characterized by low mood, hopelessness, and sadness1 that affects your daily life for 2+ weeks. Symptoms of depression and their severity often vary by person. For example, someone with severe depression may have suicidal thoughts and require intensive care. Others may experience depression as a more mild but ongoing concern, which is also called persistent depressive disorder or dysthymia. Seasonal affective disorder (SAD), another type of mood disorder, correlates with the seasons.

You can have depression and another mental illness or addiction, too. For example, anxiety disorders often co-occur with depression,2 and bipolar disorder includes episodes of severe depression as a primary symptom. Depression can also occur by itself, with the DSM-5 listing distinct symptoms like

- A loss of interest in daily activities

- Weight loss or weight gain without trying

- Feeling a sense of worthlessness and having low self-esteem

- Sad or hopeless mood most of the day

It’s vital to seek a diagnosis from a healthcare professional to determine the type of depression you may have, the prevalence of your symptoms, and the types of treatment available.

Is Depression Caused by Chemical Imbalance?

Sometimes, yes. An imbalance of neurotransmitters in the brain can poorly affect your mood3 and cause clinical depression. Common messaging around depression often places specific blame on low levels of dopamine and serotonin. But, this popular ‘blanket cause’ of depression is becoming less and less validated.

Harvard Medical School, for example, says,

Depression doesn’t spring from simply having too much or too little of certain brain chemicals. Rather, there are many possible causes of depression,3 including faulty mood regulation by the brain, genetic vulnerability, and stressful life events.

Chemicals and neurotransmitters are part of the picture, but not nearly all of it. For instance, antidepressant medications raise neurotransmitter levels immediately, but it takes weeks to see results. Ongoing research finds new nerve connections must form and strengthen in the brain to bring relief—not just balancing out neurotransmitters.

Explore Depression Treatment Centers

What Is the Leading Cause of Depression?

Everyone reacts differently to life events, adversity, and abuse. Similarly, everyone has their own unique levels of neurotransmitters and nerve connections in the brain. That’s why a singular leading cause of depression can’t be identified—but we can broadly name its causes.

8 Common Causes of Depression

1. Family History and Genetics

Depression runs in families,4 so having a family history of depression, plus other risk factors, can produce depression in yourself. Adolescents with a depressed parent are 1.5–3% more likely to develop depression than other populations. Bipolar depression has particularly high chances of affecting immediate family members. Identical twins, for example, are 60–80% likely to share their diagnosis of bipolar with the other.

Several genes affect how we respond to stress, which can increase or decrease the likelihood of developing depression. Genes turn off and on to help you adapt to life, but they don’t always adapt helpfully. They can change your biology enough to lower your mood and cause depression, even if it doesn’t run in your family.

2. Medications

Depression and medical illnesses commonly co-occur,5 which led researchers to wonder if medications and their side effects could cause depression (unrelated to the distress of medical conditions). They found that to be the case in some situations.

Several medications were found to potentially cause depressive symptoms6 and clinical depression. Medications can also cause symptoms like fatigue, sleepiness, or low appetite, which can progress into depression.

3. Trauma

Trauma can increase your risk of depression. For example, 80% of those who experienced a major negative life event developed an episode of major depression,7 and depression is 3–5 times more common in people with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)8 than without. A traumatic event could include abuse, loss of a loved one, natural disasters, job loss, witnessing or being part of violence, and homelessness.

4. Abuse

Physical, psychological, and sexual abuse can cause depression.9 Abuse can change how you see yourself and the world around you, which can lead to feelings of sadness, low self-worth, and hopelessness. Those feelings can then contribute to, or solely cause, depression.

Survivors of abuse may also isolate themselves and shut down, which can make depression more likely to develop. Emotional abuse and childhood abuse tend to correlate strongly with adult depression.10 Largely, any kind of abuse makes the development of depression more likely.

5. Pregnancy and Menopause

Pregnancy can lead to postpartum depression10 due to a sudden change in hormones, stress, and sleep deprivation after birth. Between 10–20% of new mothers develop depression. Like trauma and abuse, pregnancy can make the likelihood of depression higher, but not guarantee its development.

Menopause (the ending of a person’s menstrual cycle) causes similar changes in hormones. That, combined with other bodily and life changes common with aging, can lead to depression.

6. Illness

Depression is more common in those with physical illnesses11 like diabetes, autoimmune diseases, heart disease, and chronic pain. Feeling hopeless, unwell, and discouraged because of a health condition contributes to depression developing. Short-term illness, like being hospitalized and immobile after an accident, can also cause an episode of depression. Those with chronic illnesses may experience more frequent and long-lasting depressive episodes.

Depression can reduce normal functioning, and even life expectancy, in those with co-occurring physical illnesses. Treatment for depression can improve symptoms of physical ailments, too.

7. Drugs and Alcohol

Drugs and alcohol can cause physical and emotional symptoms that lead to depression.12 For example, feeling dependent on a substance may cause discouragement and hopelessness, which can then progress into depression. Plus, coming down from a substance-induced high mood can make low moods even more profound.

Losing relationships due to challenges with drugs and alcohol can erode support systems and lead to isolation. Sickness and ongoing effects of substance use can make you feel physically ill, which also connects to depression.

Effective treatment for substance use disorders and depression addresses each disorder to ensure both, not just one or the other, receive care.

8. Death or a Loss

Grief can be a powerful catalyst. The loss of a loved one, sudden or not, can cause low mood, hopelessness, and intense emotional pain. Though healthy grief cycles do include pain and depression, these emotions can become severe13 and interfere with your ability to function.

Sometimes, those in grief need help from a mental health professional to navigate the loss and feelings associated with it. This is especially true for anyone with thoughts of suicide or experiencing severe loss of function (can’t get up in the morning, can’t work, can’t eat).

Any of the above causes can lead to depression, but this list is far from exhaustive. Recognizing any of these causes in your life doesn’t mean you’re guaranteed to get depression, either. But they can explain why you feel how you feel, and even guide you towards more relevant treatment.

Can You Develop Depression?

Anyone can develop depression. It’s most common in young adults,14 but anyone of any age, sex, and race can become clinically depressed. You don’t need a history of depression, nor get depression by a certain age, to develop it.

Depression can come on suddenly, or as a gradual build-up of symptoms. For example, the loss of a loved one and other uncontrollable traumas could spur a quick onset of depression, while stress and anxiety can more slowly progress into depression. In cases like these, depression isn’t always noticeable until it’s glaring.

Thankfully, treatment can meet you wherever you’re at.

How Is Depression Treated?

The treatment options for depression are as vast as its causes. But to boil it down, here are some of the most common approaches to treating depression:

- Medications: A psychiatrist (a doctor in psychiatry) can prescribe antidepressants, which typically reduce symptoms in about a month’s time. It can take some patience and finagling to find the correct dosage and medication, but the results can be life-changing.

- Therapy: Attending psychotherapy in a group or 1:1 setting can improve symptoms of depression. Common therapies for depression include cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), which aims to improve unhealthy thought patterns, and dialectical behavioral therapy (DBT), which focuses more on managing emotions and thoughts in a healthy, productive way.

- Alternative treatments: Nowadays, there’s much more to treating depression than medications and talk therapy (though both can be extremely helpful.) Ketamine treatment, spiritual guidance, yoga, and transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), a gentler form of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), can all contribute to your healing.

For severe or treatment-resistant depression, you may benefit from a residential depression treatment center. Here, you’ll spend 21+ days immersed in therapy, education, and skill-building with others in the same boat as you. Partial-hospitalization programs offer intensive care too, but you can go home at night—similar to a day in school.

Psychiatric hospitals offer a safe space for those experiencing suicidal ideation, which means they have a plan and desire to attempt suicide. Short periods of stabilization here often lead to starting a residential or outpatient program, depending on your needs.

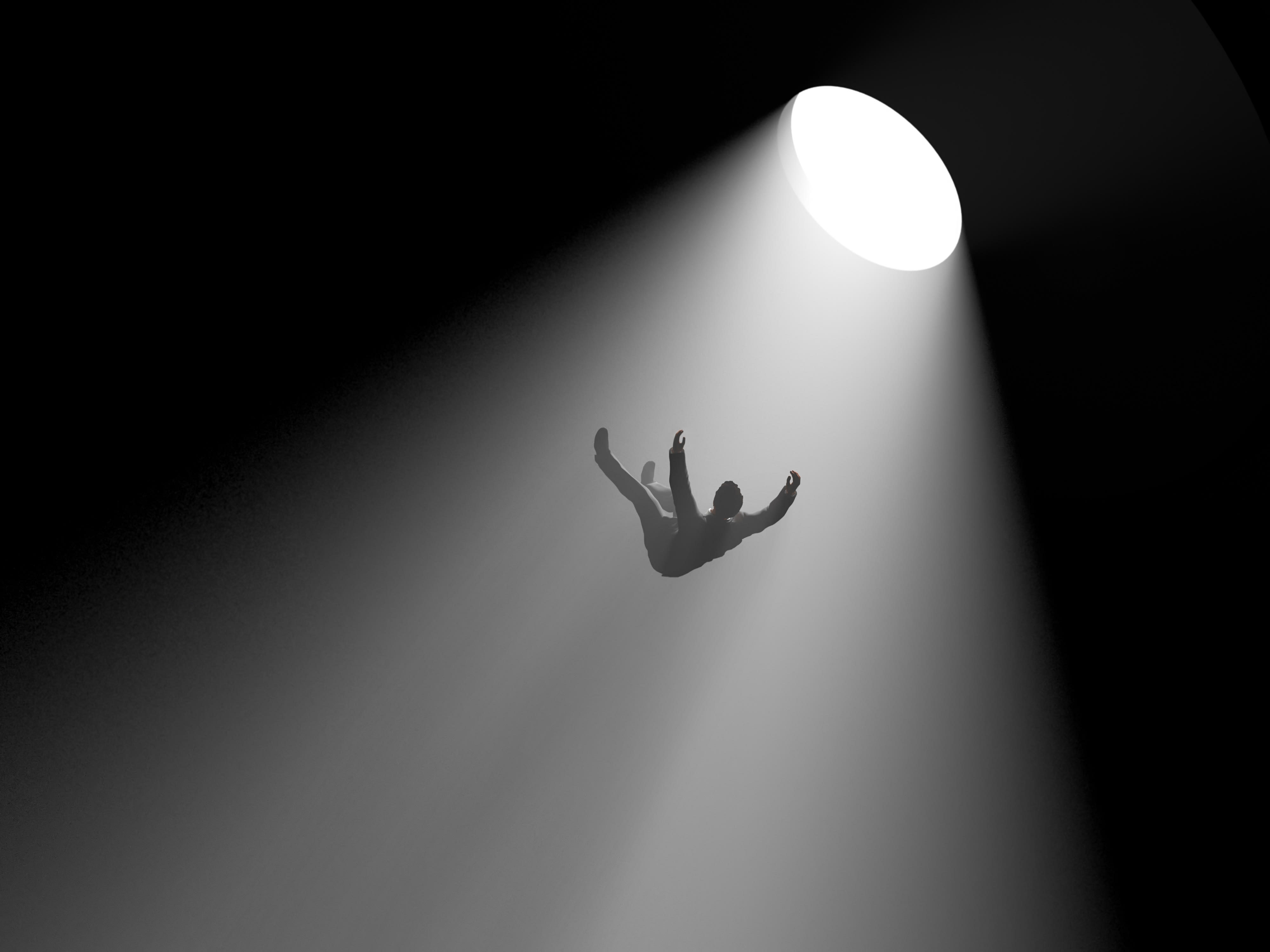

Escape the Dark: Find Help for Depression

Navigating depression isn’t something you have to do on your own. You can begin your journey by talking with a therapist or your primary healthcare provider, who can refer you to an appropriate treatment program. A psychiatrist may also prescribe antidepressants to work in tandem with therapy.

You can also attend a treatment program for depression. Browse our collection of depression treatment centers to find a facility that fits your needs—see what insurance they accept, reviews, photos, and more.

FAQs

Q: What are the main causes of depression?

A: The main causes of depression include genetics, trauma, abuse, and negative life events like job loss or losing a loved one.

Q: How can I tell if I’m depressed?

A: A mental health professional can most accurately determine if you have depression. But if your symptoms concern you and you feel like something’s not right, it probably isn’t.

Q: What is clinical depression (major depressive disorder)?

A: Clinical depression defines a period of 2+ weeks where you meet at least 5 of the diagnostic criteria for major depressive disorder. A health professional diagnoses this.

Q: When should I see my healthcare provider about my depression?

A: You should see your healthcare provider as soon as your symptoms start causing distress and concern. Don’t wait until it’s unbearable—the sooner you get help, the sooner you can feel better.

Q: What are the biological factors that contribute to depression?

A: Biological factors like age, genetics, physical health, and hormones can all contribute to depression.

-

Depression - National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/depression.

-

Kalin, Ned H. “The Critical Relationship Between Anxiety and Depression.” American Journal of Psychiatry, vol. 177, no. 5, May 2020, pp. 365–67. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2020.20030305.

-

“What Causes Depression?” Harvard Health, 9 Jun. 2009, https://www.health.harvard.edu/mind-and-mood/what-causes-depression.

-

“How Genes and Life Events Affect Mood and Depression.” Harvard Health, 10 Jan. 2022, https://www.health.harvard.edu/depression/how-genes-and-life-events-affect-mood-and-depression.

-

Celano CM, Freudenreich O, Fernandez-Robles C, Stern TA, Caro MA, Huffman JC. Depressogenic effects of medications: a review. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2011;13(1):109-25. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2011.13.1/ccelano. PMID: 21485751; PMCID: PMC3181967.

-

Celano CM, Freudenreich O, Fernandez-Robles C, Stern TA, Caro MA, Huffman JC. Depressogenic effects of medications: a review. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2011;13(1):109-25. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2011.13.1/ccelano. PMID: 21485751; PMCID: PMC3181967.

-

National Research Council (US) and Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Depression, Parenting Practices, and the Healthy Development of Children; England MJ, Sim LJ, editors. Depression in Parents, Parenting, and Children: Opportunities to Improve Identification, Treatment, and Prevention. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2009. 3, The Etiology of Depression. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK215119/

-

VA.Gov | Veterans Affairs. "Depression, Trauma, and PTSD" https://www.ptsd.va.gov/understand/related/depression_trauma.asp.

-

Radell ML, Abo Hamza EG, Daghustani WH, Perveen A, Moustafa AA. The Impact of Different Types of Abuse on Depression. Depress Res Treat. 2021 Apr 13;2021:6654503. doi: 10.1155/2021/6654503. PMID: 33936814; PMCID: PMC8060108.

-

National Research Council (US) and Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Depression, Parenting Practices, and the Healthy Development of Children; England MJ, Sim LJ, editors. Depression in Parents, Parenting, and Children: Opportunities to Improve Identification, Treatment, and Prevention. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2009. 3, The Etiology of Depression. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK215119/

-

MacHale S. Managing depression in physical illness. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 2002;8(4):297-305. doi:10.1192/apt.8.4.297

-

Quello SB, Brady KT, Sonne SC. Mood disorders and substance use disorder: a complex comorbidity. Sci Pract Perspect. 2005 Dec;3(1):13-21. doi: 10.1151/spp053113. PMID: 18552741; PMCID: PMC2851027.

-

Barbara Okun, and Joseph Nowinski PhD. “Can Grief Morph into Depression?” Harvard Health, 21 Mar. 2012, https://www.health.harvard.edu/blog/can-grief-morph-into-depression-201203214511.

-

Lee B, Wang Y, Carlson SA, et al. National, State-Level, and County-Level Prevalence Estimates of Adults Aged ≥18 Years Self-Reporting a Lifetime Diagnosis of Depression — United States, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2023;72:644–650. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7224a1

Our Promise

How Is Recovery.com Different?

We believe everyone deserves access to accurate, unbiased information about mental health and recovery. That’s why we have a comprehensive set of treatment providers and don't charge for inclusion. Any center that meets our criteria can list for free. We do not and have never accepted fees for referring someone to a particular center. Providers who advertise with us must be verified by our Research Team and we clearly mark their status as advertisers.

Our goal is to help you choose the best path for your recovery. That begins with information you can trust.